Informal microfinance in Vietnam

Mr. Hung Nguyen from the Woodberry Forest School discusses the results from his “Research in Informal Microfinance in Vietnam: Analysis and Suggestions” paper.

Informal microfinance is defined as contracts and/or agreements conducted between individuals. My “Research in Informal Microfinance in Vietnam: Analysis and Suggestions” paper showcases the situation in Vietnam, a typical developing nation, and reveals what “Informal Microfinance” can do in tackling poverty.

Primary sources

In a survey of financial practices among the poor, Collins et al. (2010) reported that most financial microloans are interest-free. Similarly, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor survey by Bygrave (2004) reported that 60-85 per cent of all lenders who are relatives or friends of the entrepreneur they financed are willing to accept low or negative returns. Surprisingly, the government itself did not see the positive changes informal microfinance brought to the economy. Nicolas Lainez, a research associate at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, wrote: “In the euphoria generated by the outstanding success of ‘Doi Moi’, the Vietnamese authorities have acted as if the informal sector did not exist or was bound to disappear.”

Limitations of data

My Google Forms survey asked various questions that assessed micro-lending history, size, performance, and effectiveness with business purposes. The convenience sampling survey was sent to 125 Vietnamese in Ho Chi Minh City ranging from 17 to 55 years of age with various jobs. These results must be interpreted with caution, and two limitations should be borne in mind: sampling bias and insufficient sample size. I had limited ability to gain access to the geographic scope of participants, here being other provinces and the countryside. In addition to that, my sample is not considered representative of the Vietnamese population, with a diversity of economic conditions.

Important findings

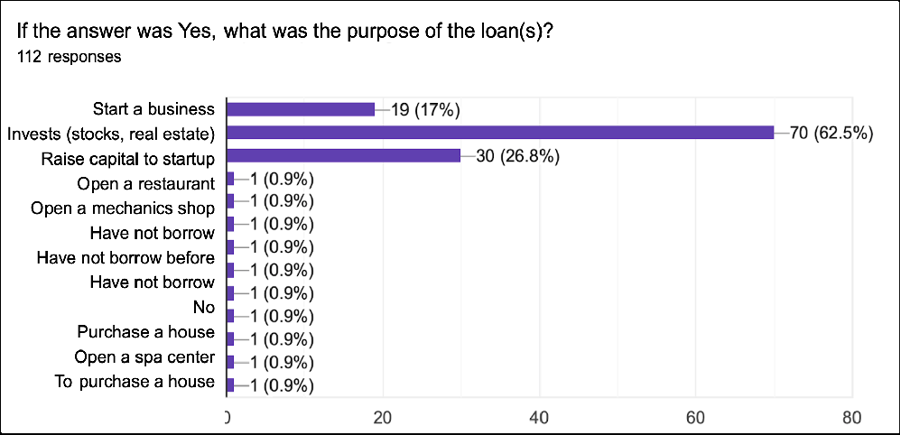

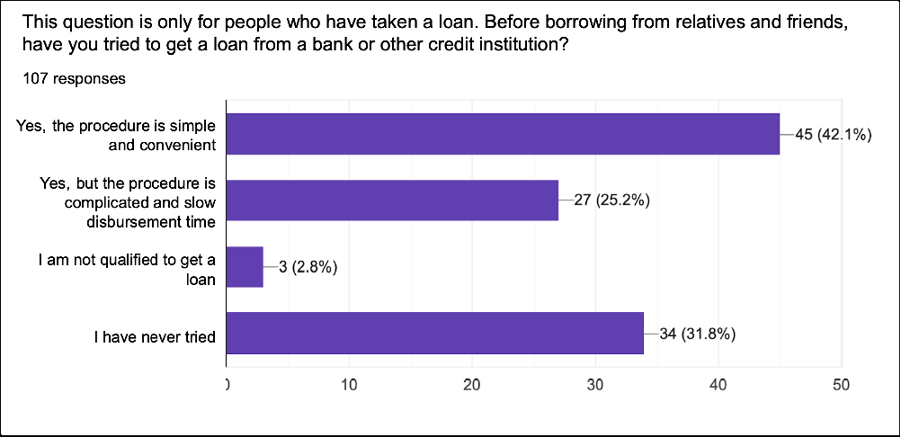

When asked about the purpose of their loan(s), all responses were typical as to why one would take out a loan from a bank. I was interested in why they chose informal practices over going to a banking institution; a much more trustworthy option.

A common explanation is that informal credit offers flexibility and is easily accessible. Those who require small loans efficiently borrow from informal markets. Terms and conditions are diversified, flexible, and timely. Therefore, the purposes given in the responses parallel the reasons people chose the informal method. I asked whether they have tried the formal method before, and 34.6 per cent answered “No”. These people have never gone to a bank to take out a loan. The inability to post collateral, lack of credit history, financial illiteracy, or insecure property titles take many poor people out of formal credit. This leaves interpersonal loans based on social ties as their only option.

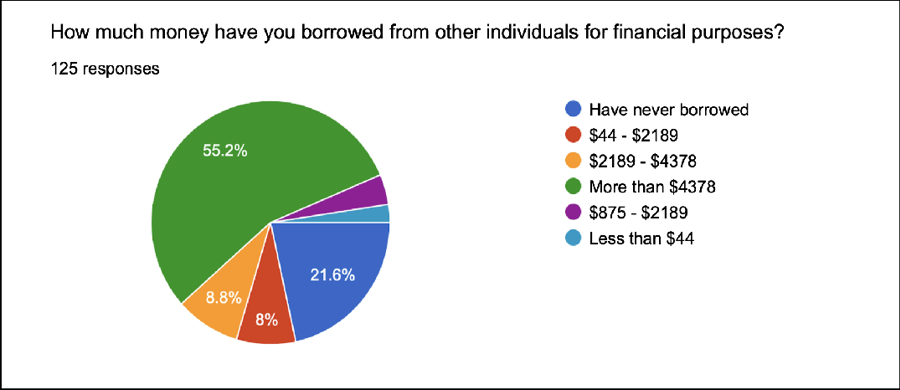

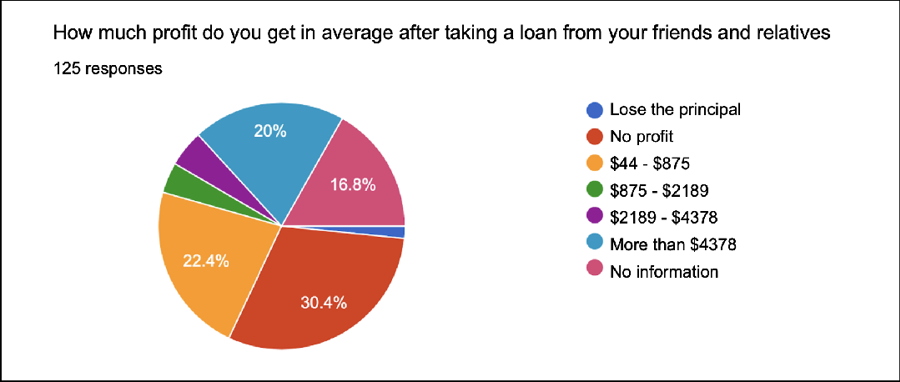

To examine the economic impact of informal microfinance, in this case microloans, I asked about the amount of money they borrowed and the amount they profited from that loan.

As can be seen from the charts, the amount of loans is not small. In fact, 68 people (55.2 per cent) borrowed more than $4,400. The median profit was $1,378. GDP growth in this sector is 31.32 per cent. Meanwhile, the highest official GDP growth in Vietnam’s history is 8.4 per cent, according to “Financial Turbulences in Vietnam’s Emerging Economy”. “Informal Microfinance” grew almost four-fold more than all other sectors combined.

In terms of long-term continuity, Vietnamese people’s caring and selflessness will continue this tradition. Informal microfinance began after the American War, specifically during the “Doi Moi” era. The market has been growing stronger due to the tight bonds between the people of Vietnam. And there is no sign that this tradition will slow down as the economy gains more momentum and individuals build up their personal wealth.

Suggestions

Microfinance and Research Institutions: The shortcomings of my research could be enhanced if a microfinance or research institution such as the World Bank could further this study. By having better approaches to surveys and the resources to facilitate the research, their findings would reveal much more about the real status quo of the informal microfinance practice in Vietnam. Once arriving at reliable findings, these institutions could design viable solutions to tackle poverty more effectively, using the resources available within these countries.

Educational microfinance communities: Those who have successfully lent or borrowed money could form groups and communities on social media to share tips and advice to future lenders and borrowers. They could share how to make the best use of the money on investments and business opportunities. In turn, the borrowers will one day end up being the lenders and continue giving advice to the next generation.

The media is the perfect gateway to raise awareness among people and governments. Not only could they share accounts from experienced practitioners, they could also host talk shows with microfinance experts to elaborate on how people could join in. They could also broadcast these stories to present opportunities on how to financially leverage their businesses.

In my next step at college, I will team up with friends to leverage this ambition further, starting from Vietnam and then to developing countries across continents. I will seek financial sponsorship to turn these suggestions into reality, to help those in need as well as help ourselves “learn by doing” real work, “giving back to society” even before we are financially affluent.